Does Wilson Have a Proper Sexual Harassment Policy?

March 5, 2020

Bruins of all grades were made aware of a new dress code standard at various beginning-of-the-year, new-principle assemblies: Business Casual. Business casual translates into toned-down professionalism; it translates into khaki pants and sports tees but no midriffs or rips at the knees or short shorts that highlight curves. While the business casual mandate seemed to change a small amount of what students were wearing, one thing did not change: the sexualization and predation of women on campus. One example of this comes from a friend of mine who bought a pleated skirt, in line with the dress code, to wear to school. This pleated skirt, commonly called the “School-Girl Skirt,” is considerably longer than what is in style today (for the sake of retro fashion) and screams business casual attire, but this student cannot wear it without receiving north of three cat-calls. At school, from students. The reason is this, the typical process of men determining what is and what is not to be sexualized (and whether or not they should verbalize it) is deeply esoteric. It depends on culture, on media, what can be fetishized, and of course, what is plainly revealing.

The Me Too Era ushered in hard truths, survivor bravery, greater openness to it’s discussion topic, and a need for more localized, specific examining of the issue. In other words, while the Me Too movement has done a lot for our national culture, it sometimes lacks weight when used to discuss our offices, our cities, our schools.

At Wilson, female students (while all genders can be equally objectified) are catcalled. Some boy students make unsolicited sexual comments in the hallway and, less often, non-consentingly touch them in places ranging from the shoulder to awfully less negotiable places. Groping, calling, shouting. Women and girls are used to it and the Me Too movement made that gloomy fact known. But, again, it takes deeper hits at the local level. For example, it takes a deeper hit when the uniform-expectations part of our beginning-of-the-year assembly uses language in the slide-show presentation and includes dialogue in the administration’s speeches specifically geared toward women,“Ladies, your shorts must not be shorter than here.”. It takes deeper hits when girls abide by the uniform, when girls dress business casual, when girls are still harassed, and it is still treated as their fault. The official Dress Code reads: Girls’ shirts should not be too tight / skin or belly button should not show.

I would like to request better elaboration on the use and framework of the word “skin.” I would like to know which location of skin is this is in reference to and what location of skin is particularly offensive. Because to say “midriff may not be exposed when arms are raised,” under a girl-only section absolutely negates the fact that when a boy lifts up his arms, you see both his stomach and his underwear brand.

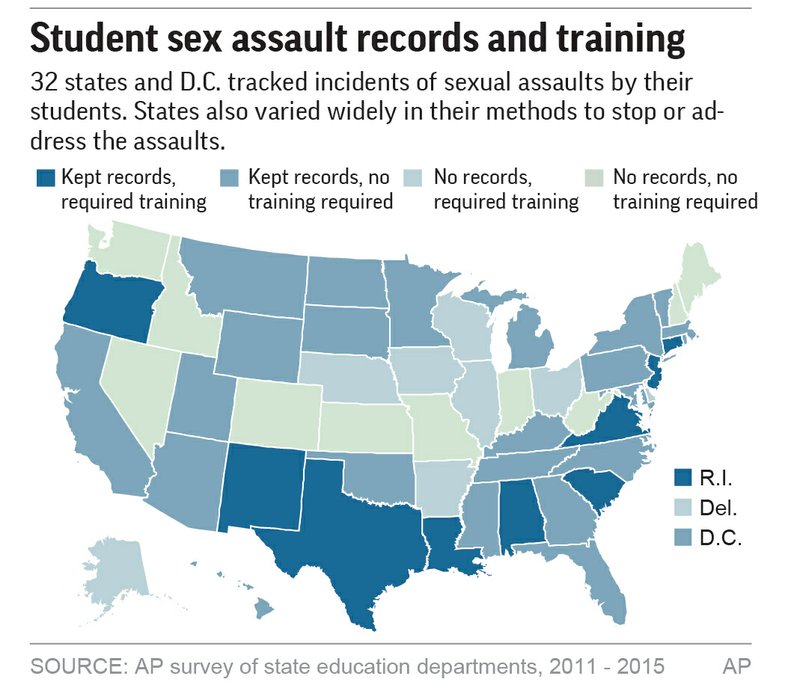

In the Me Too era, do schools have proper outlets for those students who are sexaully assualted? Do schools have protocol to follow when a student makes an unwanted, sexual comment to another student in class? Is that student moved to another class, is that student suspended? The Atlantic found through various victims in U.S. K-12 schools that speaking up to school administration about on-campus sexual assault largely results in the victims themselves being punished. It is also to be noted that roughly 80% of K-12 guidance counselors felt inadequate in dealing with student’s reports of abuse– suggesting a lack of training in addressing such significant and relevant issues. These statistics are, however, a generalization of U.S. K-12 schools as a whole. It is possible that your specific school is better or worse equipped to deal with incidents of sexual assault or harrassment on campus. The LBUSD district, for example, has specific in-place protocol for dealing with sexual assault. The LBUSD website cites, “Any employee who receives a report or observes an incident of sexual harassment shall notify the principal or the Title IX district compliance officer. Once notified, the principal or compliance officer shall take the steps to investigate and address the allegation, as specified in the administrative regulation (AR 1312.3 Uniform Complaint Procedures)”. After investigation, undisclosed actions will be taken (“The Superintendent or designee shall take appropriate actions to reinforce the district’s sexual harassment policy”).

This policy, while implemented, could possibly be better expressed within the district’s schools. It is important that policy is openly understood, so that students understand policy is in place at all, and vitcims feels they can recieve help. To investigate policy, if it is effective or in place at all, on your campus turn to the words of anti-sexual violence organization Break the Cycle’s Director of Programs, Kelley Hampton, for a U.S. News & World Report article, “It’s really important that they have a policy in place, and that that policy is clear and has been communicated to the entire school community. That is the most important, best practice and that is what we see is most lacking.” It is important to ask if your school clearly communicated consequences for unsolicited, non-consensual sexual activity, as much as it has clearly communicated the consequences for being out of dress code or other misdemeanors.

At least a part of the reason sexual assault is so present is because people feel they can get away with it. They have read an internal dialogue, expressed by current policy-making, that says: we do not punish these acts because we do not respect their victims; we do not respect their victims, so you do not have to either. Students must address whether or not their school is contributing to that dialogue.